CASE STUDIES

To help optimize learning, each section of the case study has a review test with feedback for both correct and incorrect answers to help you better understand.

Click here or any panel below for a PDF of all Case 2 panels and screens >

CASE STUDY 2

Matt Hukill,

Product Manager, Hemo bioscience, Inc.

SECTION 1

Background:

MW, a 45-year-old elementary school art teacher, recently scheduled a hysterectomy with her gynecologist to address increasingly problematic uterine fibroids that have been affecting her quality of life for the past year. MW, who has always been passionate about her students and her art, first noticed that her energy levels began declining noticeably about eighteen months ago, but initially attributed this to the demands of teaching and getting older.

Over time, MW's symptoms progressively worsened, with heavy menstrual bleeding becoming so severe that she started missing several days of work each month. Because she loves her job, MW had only taken three sick days in her previous ten years of teaching. She decided she needed to address the issue when she started to struggle to maintain her enthusiasm for the after-school art club she founded and has run for the past eight years. When her hemoglobin dropped to 8.1 g/dL despite iron supplementation, both MW and her physician agreed that surgical intervention was necessary.

MW's medical history is significant for three pregnancies, resulting in two healthy children now aged 20 and 17, and one pregnancy that ended in a miscarriage at 12 weeks. Her third pregnancy, which resulted in the birth of her younger child, was complicated by severe postpartum hemorrhage that required transfusion of 2 units of red blood cells. MW recalls being told at the time that her blood type was common and that finding compatible blood was not a problem. She has no other history of transfusions and takes only a daily multivitamin and iron supplements.

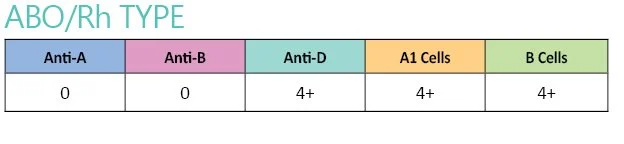

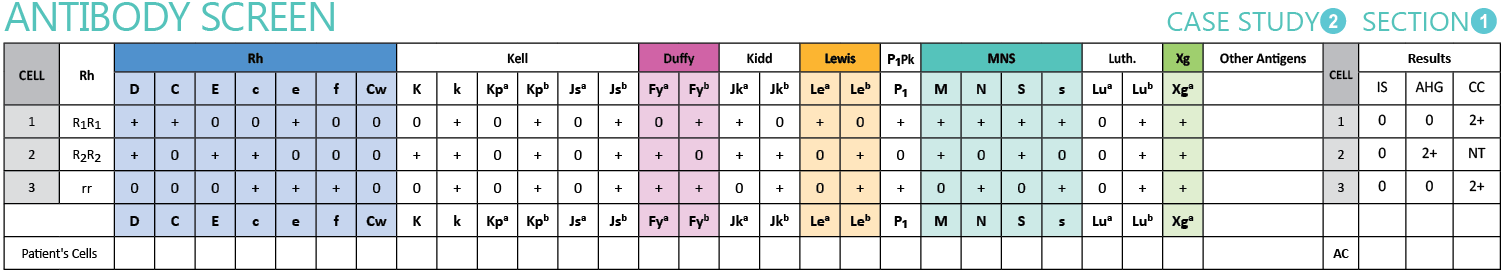

MW's routine laboratory testing includes a complete blood count and a type and screen to determine the quantity and availability of crossmatch compatible blood needed for her upcoming surgery. Her surgeon explained that while hysterectomies typically do not require transfusion, it is standard practice to have blood available given her current anemic state and history of hemorrhage during her previous delivery.

SECTION 2

Investigation:

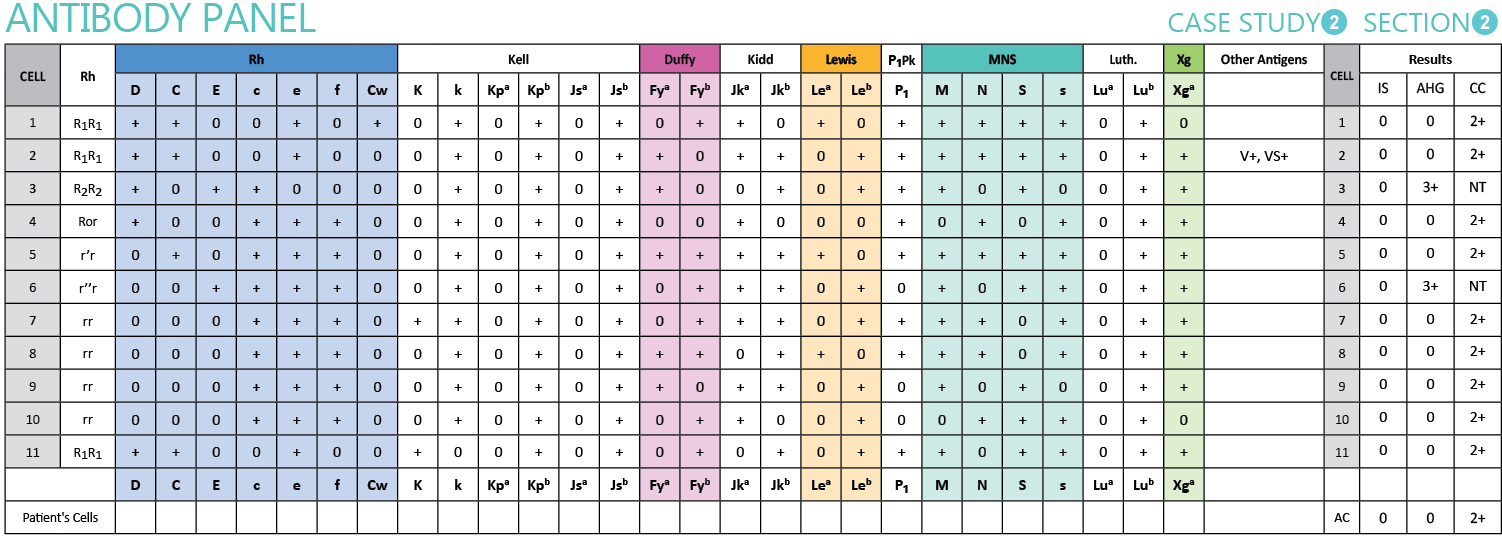

An antibody identification panel was performed to determine the specificity of the antibody detected in the antibody screen.

SECTION 3

Investigation:

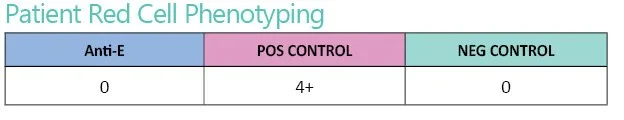

Following antibody identification, MW's red cells were tested for the E antigen with Anti-E antisera to confirm the antibody specificity.

SECTION 5

Investigation:

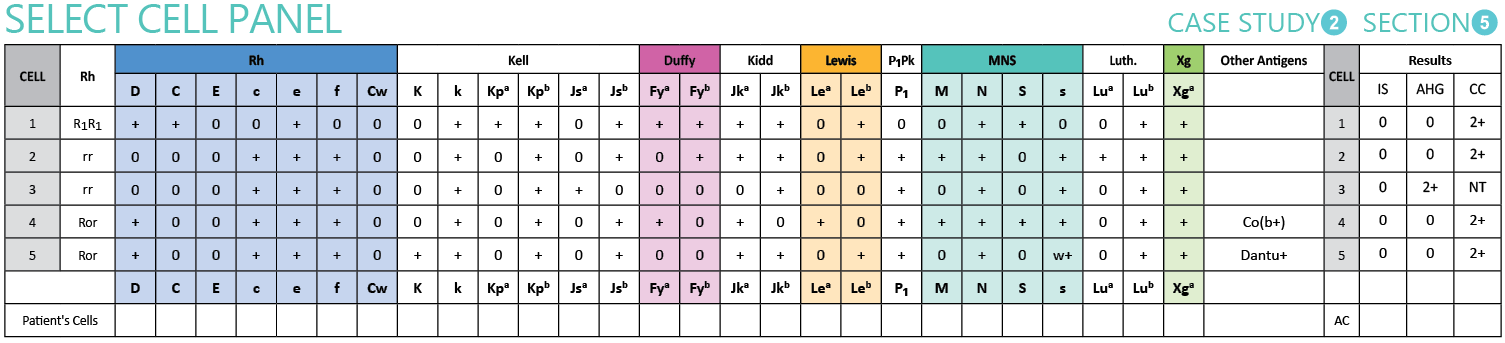

The blood bank technologist performed a select cell panel using the panel cells they had available that are negative for the E antigen and positive for a unique low prevalence antigen, hoping to see if any of them reacted and gave a clue about the specificity.

SECTION 6

Investigation:

To provide preliminary confirmation of the suspected Anti-Jsa, a second E-negative, Js(a+) reagent red cell was tested against MW's plasma.

The second Js(a+) cell also demonstrated reactivity at the AHG phase, which is enough evidence to determine a likely specificity. However, since Anti-Jsa antisera is not commercially available, MW's sample will need to be sent out to an immunohematology reference laboratory (IRL) or molecular testing for final confirmation.

SECTION 4

Investigation:

Based on the Anti-E identification and MW's E negative phenotype, the blood bank selected two units of group O, RhD positive, E negative red cells for compatibility testing.

CONCLUSION

MW's case is an example of the importance of testing that goes beyond routine antibody screens. While effective at detecting most clinically significant antibodies, antibody screens have limitations, such as detecting antibodies to low prevalence antigens. MW developed two clinically significant alloantibodies: Anti-E, which was readily detected by routine screening, and a probable Anti-Jsa, which was only discovered during compatibility testing when a Js(a+) donor unit was randomly selected.

The select cell panel testing provided evidence for Anti-Jsa specificity, and preliminary confirmation with a second Js(a+) cell supported this identification. Final confirmation and patient phenotyping will be completed by the immunohematology reference laboratory, as Anti-Jsa antisera is not commercially available for routine laboratory use.

Anti-Jsa is a clinically significant antibody in the Kell blood group system that can cause hemolytic transfusion reactions and decreased red cell survival. The Jsa antigen has a prevalence of less than 1%, making it unlikely to be present on routine reagent antibody screening or panel cells. This is an example of why crossmatch testing at the AHG phase is important in patients known to have produced an antibody to a red cell antigen, even when common antibodies have been ruled out. Unexpected antibodies can still be discovered that would compromise transfusion safety.

The IRL will provide group O, RhD positive red cells that are negative for the E and Jsa antigens for MW’s scheduled hysterectomy. An emergency transfusion plan for MW includes transfusing ABO/Rh compatible, E negative, AHG crossmatch compatible units if significant, life-threatening bleeding were to occur before units from the IRL arrive. In an emergency, Unit 1 from the original crossmatch remains suitable for transfusion, and more units can be crossmatched with MW’s plasma at the AHG phase if necessary.

Questions, answers, and helpful feedback submitted after completing the Case Study Review will be posted here.